Dr. Martin Luther King’s Visit to Cold War Berlin

Tracing an Untold Story: Dr. Martin Luther King’s Visit to Cold War Berlin. East or West – God’s Children

“Here in Berlin, one cannot help being aware that you are the hub around which turns the wheel of history. For just as we are proving to be the testing ground of races living together in spite of their differences, you are testing the possibility of co-existence for the two ideologies which now compete for world dominance. If ever there were a people who should be constantly sensitive to their destiny, the people of Berlin, East and West, should be they.”

When invited by West Berlin Mayor Willy Brandt in 1964 to open the 14th annual cultural festival of the city, which had prepared a triumphant welcome for President John F. Kennedy only one year before, Dr. Martin Luther King used the opportunity to extend his spiritual message of brotherhood to the situation of Cold War Berlin, arguing that although the city “stands as a symbol of the division of men on the face of the earth,” it was clear that “on either side of the wall are God’s children, and no man-made barrier can obliterate that fact.”

Dr. King’s visit to Cold War Berlin in September 1964 had been prepared by Willy Brandt’s 1961 visit to the U.S. and his meeting with King. Another important facilitator was Provost Heinrich Grüber, the former pastor at East Berlin’s St. Mary’s Church. Grüber had been an active opponent of the Nazi regime, gaining international attention when he testified during the trial of Adolf Eichmann, one of the leading architects of the Holocaust, in Jerusalem in 1961. Invited by U.S. churches, Grüber began to travel across the U.S. delivering sermons in the following years. He also met with Attorney General Robert Kennedy, and encountered the African-American struggle for civil rights firsthand. Perceiving this struggle as similar to his resistance to fascism, Grüber took up correspondence with Dr. King, already inviting him to Berlin in the course of 1963.

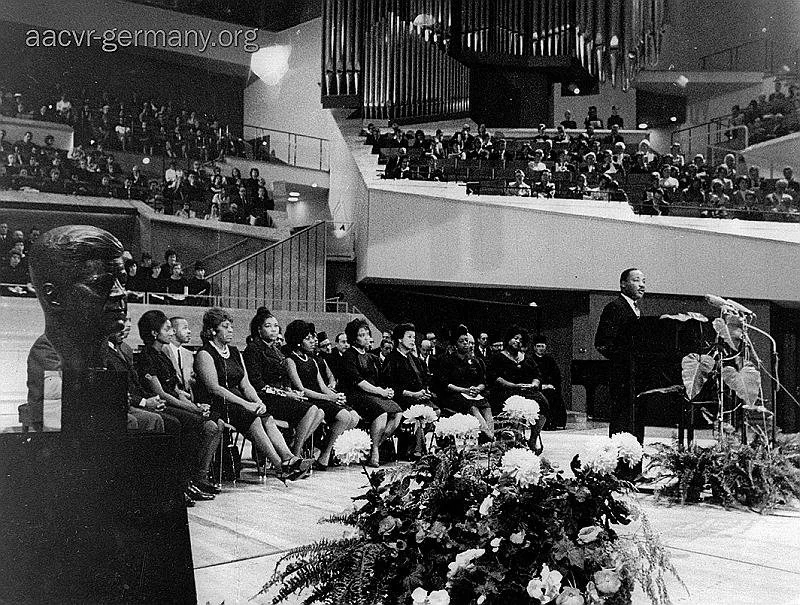

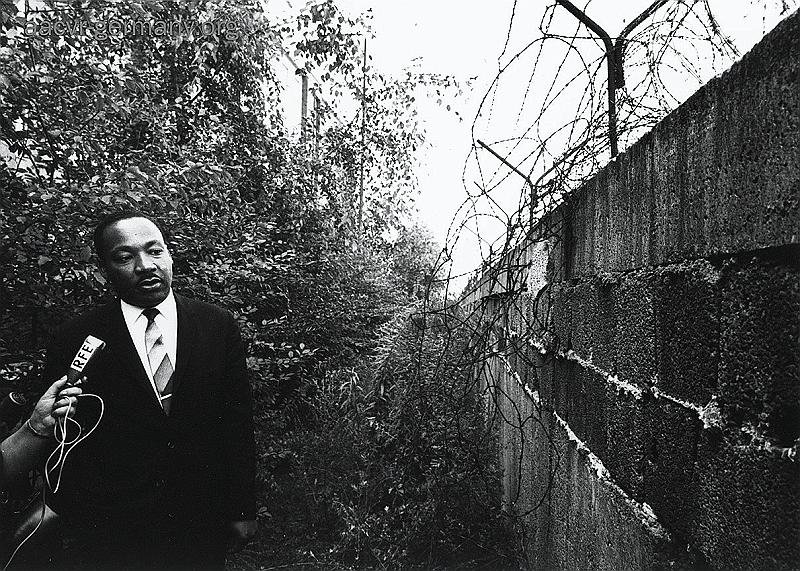

In his one and a half days in the city, Dr. King completed a whirlwind tour. He visited the Berlin Wall, where only the day before an East German had escaped to the West, provoking a gun battle between U.S. soldiers and East German border guards. King opened the city’s cultural festival that also included a memorial service for John F. Kennedy at the Berlin Philharmonic Hall, delivered a sermon to more than 20,000 West Berliners at an outdoor arena, and was awarded an honorary degree by the Theological School of the Protestant Church.

Most spectacularly, even without a passport, King managed to cross the border at Checkpoint Charlie into East Berlin, where he preached to an enthusiastic crowd in the overflowing St. Mary’s Church at Alexander Square about the struggle for civil rights in his own country, bringing greetings from the “Christian brothers and sisters” both from the United States and West Berlin. Since so many (especially young) people came to see Dr. King, he had to hold another service in the nearby Sophia Church for almost 2,000 people. Afterwards, he met with students from Humboldt University and church officials before returning to the sector of the city controlled by the Western Allies.

Although Dr. King refrained from making any comments about the political situation in Germany, his visit undoubtedly sharpened his belief in the “common humanity” that binds people together “regardless of the barriers of race, creed, ideology, or nationality.” As he argued in his speeches in both parts of the divided city, “Whether it be East or West, men or women search for meaning, hope for fulfillment, yearn for faith in something beyond themselves, and cry desperately for love and community to support them in this pilgrim journey.”

Only three months later, when invited to Oslo in December 1964 to accept the Nobel Peace Prize, Dr. King referred once again to globally significant themes that continue to resonate today: racial injustice, poverty, and war. In a world threatened with nuclear extinction and the Cold War confrontation between East and West, Dr. King argued that, “In one sense the civil rights movement in the United States is a special American phenomenon which must be understood in the light of American history and dealt with in terms of the American situation. But on another and more important level, what is happening in the United States today is a relatively small part of a world development.”

King claimed that all human beings were tied together in a “world-wide fellowship,” and that “However deeply American Negroes are caught in the struggle to be at last at home in our homeland of the United States, we cannot ignore the larger world house in which we are also dwellers.”

Although historical memory has largely ignored Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s visit to Cold War Berlin, his appearance there and his message of peaceful social revolution not only inspired Germans on both sides of Iron Curtain. It also stands as yet another symbol for the global reach and impact of the African-American civil rights movement.

For Germans of all ages, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. became an icon of civil and human rights during the Cold War who exposed America’s failure to fulfill its democratic promise. When he was murdered on April 4, 1968, Germans across the country gathered in mourning to them, King represented a voice for a better America that spoke to people’s aspirations worldwide. When Barack Obama addressed more than 200,000 enthusiastic Berliners during his presidential campaign in 2008, the German press therefore evoked not only the memory of John F. Kennedys visit to the city in 1963 but also that of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. the following year.

Chronology of Dr. King’s Visit to Berlin

September 12, 1964

3 pm:

Arrival at Tempelhof Airport and Welcome by West Berlin Government and Church Officials Press Conference at the West Berlin Senate Guest House, Grunewald

September 13, 1964

10 am:

Reception at West Berlin City Hall with Mayor Willy Brandt and Signing of the City’s Golden Book

11 am:

Opening of the 14th Annual Cultural Festival with a Memorial Service for John F. Kennedy at the Berlin Philharmonic Hall

1 pm:

Reception at the Foyer of the Berlin Academy of Arts hosted by West Berlin Senator for Arts and Science, Dr. Werner Stein

3 pm:

Open Air Church Rally and Sermon at the “Waldbühne” (20,000 people)

Visit to the Berlin Wall (Bernauer, Schwedter and Stallschreiber Street)

5.30 pm:

Award Ceremony for an Honorary Degree of the Theological School of the West Berlin Protestant Church in the home of Bishop Dr. Otto Dibelius

7 pm:

Border Crossing at Checkpoint Charlie 8 (Friedrich Street)

8 pm:

Church Service in East Berlin’s Marienkirche (St. Mary’s)

10 pm:

Additional Church Service at the Sophienkirche (Sophia Church) in East Berlin and Meeting with Leading Representatives of the Protestant Church Berlin Brandenburg at the Hospice Albrecht Street

11 pm:

Return to West Berlin and Late Dinner at Guest House Grunewald

September 14, 1964

End of Visit and Onward Journey to Munich

Primary Sources:

“East and West – God’s Children,“ Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.: Sermon at the Marienkirche, East Berlin, September 13, 1964

For a transcript of the sermon, please see here.

“Resisting Injustice Then and Now,“ Heinrich Grüber to Dr. Martin Luther King, letter (July 15, 1963)

“A Signal of Freedom from Cold War Berlin,“ West Berlin Mayor Willy Brandt at the opening of the city’s annual cultural festival (September 13, 1964)“Crossing the Border at Checkpoint Charlie,“ Ministry for State Security, Main Office for Passport Control and Searches, Friedrich-/ Zimmer Street, Berlin, (September 13, 1964) (BSTU)

“A Message of Hope in East Berlin,“ Alcyone Scott, one of Dr. King’s translators during his visit, on his sermon in St. Mary’s Church in East Berlin, Interview (June 8, 2009)

“On the Importance of Jazz,“ Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Opening Address to the 1964 Berlin Jazz Festival.

> moreInterview with Martin Luther King, Jr. on his visit to Berlin, “Seine Waffe ist Gewaltlosigkeit,” B.Z. (September 14, 1964).

> more“Dr. Luther King: ‘Um Berlin dreht sich heute die Weltgeschichte’,” in: BILD-Zeitung (September 14, 1964).

> more

Further Reading:

Appelius, Stefan: “Let my people go,“ in: einestages / SPIEGEL online, September 13, 2009.

Appelius, Stefan: “My dear Christian friends in East Berlin,“ in: www.chrismon.de.

“30. Jahrestag – USA: Martin Luther King in Memphis/Tennessee ermordet am 4. April 1968,“ Deutsches Rundfunkarchiv (DRA), April 04, 1998

Educache zu Martin Luther King auf RBB und ARD, Dotcom-Blog, April 17, 2010

Meusel, Georg: “Mit Kreditkarte über die Mauer,“ in: Der Freitag, September 24, 2004.

Stolte, Roland: Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1964 in Berlin (September 2009).

> View PDF

> View PDFTharoor, Kanishk “Martin Luther King in Berlin: Marienkirche or the Brandenburg Gate?“ in: www.opendemocracy.net, April 08, 2008.

Dailey, Jane: “Obama’s Omission,“ in: Chicago Tribune, July 30, 2008.

Resisting Injustice Then and Now

“I remembered the time during the Hitler regime when my precious wife and family fought with and for me and I decided to write you. I write in the bond of the same faith and hope, knowing your experiences are the same as ours were. When Hitler published the so-called Nurnberg ‘Race Codes’, I allied myself with many pastors of the confessed church in opposition of this act and founded an office to help the suppressed and discriminated; this office bore my name. Because of this, Eichmann sent me to a concentration camp in 1940: first to Sachsenhausen, then to Dachau.

In the Eichmann trial, I was the only German Christian witness to testify, and through this, I became known in America and have received many invitations. I was in the States when the incidents in Mississippi began. I preached a sermon on Sunday in Chicago during this struggle to a Negro congregation, using the text: ‘We are all one in Christ’. During the time of Hitler, I was often ashamed of being a German, as today, I am ashamed of being white. I am grateful to you, dear brother, and to all who stand with you in this fight for justice, which you are conducting in the spirit of Jesus Christ.”

A Signal of Freedom from Cold War Berlin

“Here in Berlin, a miracle occurred—people asserted themselves, surrounded by threatening force, but borne up by the awareness that freedom is stronger. This was and continues to be more than a national task. We know that it is about freedom for all. All people, regardless of their skin color, of their faith, of their social background, of their nationality. In this spirit, we begin this Festival 1964. …

I welcome Dr. Martin Luther King, who has devoted his life to this great task with courage and determination: to further the cause of freedom and help his country, where he is struggling to achieve equality for his brothers. … I would be pleased if a message of self-confidence and hope would emanate from this place and from our festival to many peoples. Especially to the peoples of Africa as well. And over the ocean. But also into the quiet streets beyond the wall that Kennedy spoke of. To all people who strive to get past the sometimes rather narrow issues of politics and live their lives in peace and freedom and dignity.”

Crossing the Border at Checkpoint Charlie

“On 9/13/1964, Negro theologist Dr. Martin Luther King appears [at our checkpoint] … to enter [the country]. In attendance are two US citizens [first name blacked out] … and Zorn, Ralph … These two citizens state that their colleague, they did not name any names, forgot his passport in West Berlin. They now want to go to the Marienkirche for a sermon.

As Dr. King, who was not yet known at that point, was unable to prove his identity, we told him that he could not enter democratic Berlin without a passport. When the three citizens were about to go back to West Berlin, Second Lieutenant Lindemann recognized Dr. King. … Asked whether Dr. King had any other sort of passport with him, he presented a check card of the USA (similar to an identity card). …

Furthermore, Z[orn] remarked that K[ing] himself would be holding the sermon in the Marienkirche. Thereupon, the three citizens were permitted to enter after consultation with on-duty officers. All three were dispatched to the currency exchange counter. Dr. King and the others expressed their appreciation repeatedly and drove into democratic Berlin at about 19:52.”

A Message of Hope in East Berlin

“The church is absolutely packed. … And the entire time Dr. King is speaking, you could hear a pin drop. Nobody coughed, nobody sneezed. … These people are in a kind of a prison not of their own choosing. They didn’t have any freedom to claim. And he’s talking to them about passive resistance. In other words, admitting to them, ‘you are in a situation that needs to be resisted.’ And that was radical in and of itself. The church was probably the only arena in which he could have spoken in the East and been able to say what he did.

So, he gives exactly the same speech as he gave in the West, and at some point the choir sings Go Down Moses. And it was an incredible performance. But that song ends with ‘Let my people go!’ and this place was as still as if this was a prayer that everybody in that room felt. I can’t explain the power of that moment. Everybody in that church was totally wrapped up in someone whose story they knew and who represented the shame of America and its oppression but who had the courage to resist, and ask others, in their situations, also to resist.

It was clear there was power in his message couched in very clear Christian terminology. This was a man of a faith with a profound belief in humanity and in reconciliation. He believed it, and you felt it. And it was especially clear for people who really saw no future for themselves. The Cold War was hot, and no one imagined it would ever end. For him to talk about hope in this situation was electrifying. I don’t think I’ve ever been present where all of those things that one wants to believe in and desperately hope for are given expression with such resonance. This was, however, the case for the East Berliners in that church at that moment. I was never again in a situation equal to the one I was in there in East Berlin.”

Supported by St. Mary’s Church (Evangelische Kirchengemeinde St.Petri-St.Marien), Berlin, Germany