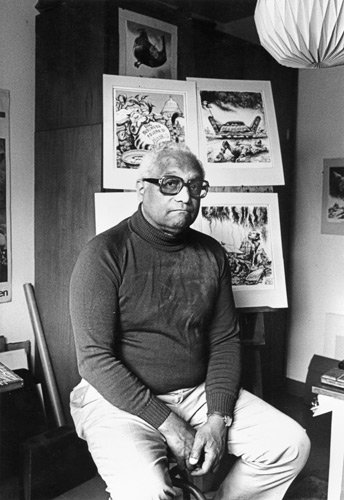

Oliver Harrington

Cartoons by Oliver Harrington

Oliver Wendell Harrington was born on February 14, 1912, in Valhalla, NY, the son of an African-American father and a Jewish mother from Budapest. Growing up in the South Bronx, an ethnically diverse neighborhood, Harrington was early on sensitized to racism in American society. From the beginning of his artistic career in 1929, he drew cartoons not only to establish a more realistic and less stereotypical depiction of African-American life but also to vent his anger about the continuing racial discrimination in the U.S. He first made his mark with explicitly political cartoons during the 1932 election, when he urged African-American voters to forsake their traditional loyalties to the party of Lincoln and vote for the Democrats and Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal policies instead.

During the 1930s, Harrington lived and worked as a freelance artist in Harlem, which was still flourishing in the afterglow of the Harlem Renaissance. In Harlem, he became part of a thriving community of black artists, among them the famous African-American poet Langston Hughes, with whom he developed a lifelong friendship. Harrington began working for the Amsterdam News, the major black newspaper in the New York area, as well as such influential papers as the Baltimore Afro-American and the Pittsburgh Courier. The latter remained one of his main employers in the following decades.

In 1935, Harrington began a satirical and often political cartoon in the Amsterdam News entitled “Dark Laughter” which recorded the absurdities and frustrations of Harlem life. In this context, he developed his best-known cartoon character: Bootsie, an ordinary African-American man coping with everyday racism in American society. Langston Hughes honored his friend’s work when he wrote the introduction for the 1958 anthology Bootsie and Others: A Selection of Cartoons by Ollie Harrington.

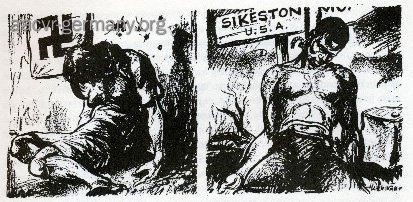

Upon receiving his bachelor’s degree from Yale University in 1940, Harrington took his first full-time job as an art director in 1942 for The People’s Voice, a self-proclaimed, “working-class paper” that was wholly owned and operated by African Americans. It was in his artistic work during World War II that Harrington exposed the discrepancy between the U.S. fight for democracy abroad and the status of African Americans as second-class citizens at home.

At the same time, he questioned the U.S. policy of fighting fascism and racism in Europe while tolerating the racism of European colonial powers in other parts of the world. In his cartoons, Harrington thus chose to illustrate uncomfortable questions by insisting that victory in World War II would also mean that America had to rethink its own system of racial segregation and discrimination.

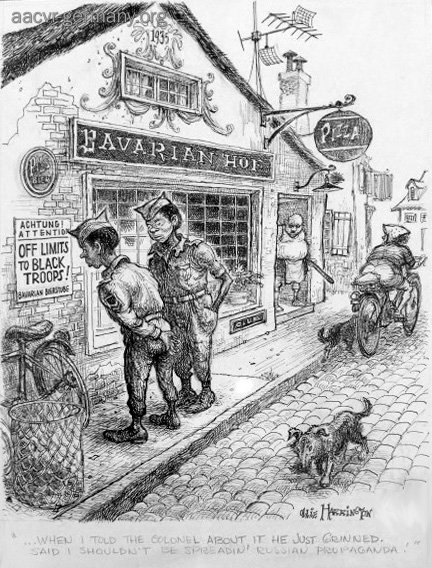

In 1943, the Pittsburgh Courier sent Harrington as a war correspondent to Europe. In Italy, he escorted Walter White, the NAACP executive secretary, to frontlines and documented the situation of African-American soldiers first hand. These experiences confirmed Harrington’s notions of World War II as a possible turning point in race relations and also introduced him to a world without a formal color line.

After the war – moved by a wave of brutal lynchings of returning veterans in the South – Harrington accepted White’s proposal to organize the NAACP’s Public Relations Department from which he was able to advocate an end to racial discrimination. In 1946, he explained that he had taken on this struggle because black soldiers had fought “to tear down the sign ‘No Jews Allowed’ in Germany” only to find that “the sign, ‘No Negroes Allowed’” was still there when they returned to their homes. “His political activism on behalf of civil rights brought him to the attention of McCarthy-era witch-hunters. As a result, Harrington left the United States in 1951 and settled in France, where he became part of an active African-American expatriate community, befriending writers such as James Baldwin, Richard Wright, and William Gardner Smith.

In 1961, Harrington was caught by the construction of the Berlin Wall when he traveled to East Berlin to accept an offer from Aufbau Publishers to illustrate a series of American literary classics that had been translated into German. He decided to remain in East Germany for the following three decades of his life, only returning to the United States for a visit the first time in 1991. In East Germany, Harrington enjoyed particularly high esteem for his skills as a political cartoonist and specialized in addressing the political situation in America and the world at large, giving frequent attention to racism, poverty, and imperialism. Both the humor magazine Eulenspiegel and the general interest periodical Das Magazin, one of the most popular papers in East Germany, used his art work on a regular basis. Throughout his life, Harrington remained a keen observer and denouncer of institutionalized racial injustice. The few works presented here provide merely a glimpse into a remarkably broad and diverse career.

As an African American, Ollie Harrington found it impossible to be an artist and not to be political. “Although I believe that ‘art for art’s sake’ has its merits,” Harrington wrote, “I personally feel that my art must be involved, and the most profound involvement must be with the Black liberation struggle.”

Further Reading

Harrington, Oliver: Bootsie and Others: A Selection of Cartoons (New York: Dodd, 1958).

Harrington, Oliver: Soul Shots: Political Cartoons by Ollie Harrington (New York: Longview Publishing, 1972).

Harrington,Oliver: Why I Left America and Other Essays (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1993).

Höhn, Maria and Martin Klimke: A Breath of Freedom: The Civil Rights Struggle, African American GIs, and Germany (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), chapter 7.

Inge, M. Thomas ed.: Dark Laughter: The Satiric Art of Oliver W. Harrington (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1993).